A Lowcountry Golf Revival

Area Clubs Are Invested in Renovation

by JG Walker

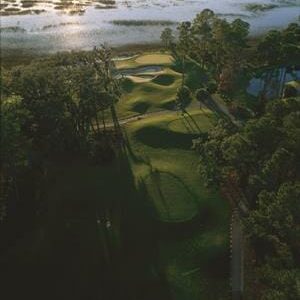

Belfair, a private golf club community in Bluffton, SC, exemplifies pure Lowcountry golf at its best.

The Lowcountry of South Carolina extends from Murrells Inlet below Myrtle Beach, south through Charleston and Beaufort to the Savannah River, east to the Atlantic Ocean, and west as far inland as the Spanish moss hangs from the trees.

America’s first golf club was established in 1786 near Charleston by presumably homesick Scotsmen, but it disbanded after about 15 years. Only a handful of private golf courses were subsequently built in the area, many of them during a spike in the game’s popularity in the 1920s. But the modern genesis of Lowcountry golf dates to 1961 when architect George Cobb designed the Sea Pines Ocean Course for new residents and tourists on Hilton Head Island. By the end of that decade, Pete Dye and Jack Nicklaus had collaborated in the building of Harbour Town Golf Links, Arnold Palmer had won the PGA TOUR’s inaugural Heritage Classic there, and the Lowcountry became a major national golf destination. Since then, more than 90 private and resort courses have opened in the coastal region, most of them built in the 1970s and ‘80s.

But with age comes change: the spreading of wrinkles, the sagging of contours, the intrusion of growth where there was none before and the weakening of foundations once taken for granted. Golf courses are like that, too.

“The lifespan of most courses is about 30 to 40 years,” said golf architect Clyde Johnston. “The range depends on the quality of the original course construction and how well it’s maintained over the years, but even the best eventually wear down from the combined impact of nature and people.”

Johnston has seen that cycle first-hand: with a degree in landscape architecture from North Carolina State University and a family-inspired love of golf, he took a job with noted course architect Willard Byrd in 1974 and moved to the company’s Hilton Head Island office in 1980. Johnston and Byrd worked together on about 50 new layouts and refurbishments before Johnston opened his own course-design company in 1987. Since then, he’s built 37 new golf courses, including award-winners like Glen Dornoch in Little River, Wachesaw East in Murrells Inlet and Old South near Hilton Head, as well as the 36-hole club at River Landing in Wallace, North Carolina, and Cherry Blossom in Georgetown, Kentucky.

“That’s why most of us came here to the Lowcountry in the first place: the clean air and water and beaches, the trees and the flowers and the wildlife. It’s a great place to raise your kids or enjoy your retirement. And to play golf. And I hope it’ll be like that a hundred years from now and that whoever is renovating one of my courses then will have the same perspective,” says golf architect, Clyde Johnston.

But along with the rest of the national economy, the golf-course design business has changed since major capital investments dried up after the 2008 recession. Many drawing-board projects still remain on paper and golf architects, like auto mechanics, have found that the repair business increases when folks decide to put off that new purchase.

But along with the rest of the national economy, the golf-course design business has changed since major capital investments dried up after the 2008 recession. Many drawing-board projects still remain on paper and golf architects, like auto mechanics, have found that the repair business increases when folks decide to put off that new purchase.

“Golf courses are like cars in that way,” Johnston said. “They’ll continue to run fine with a little timely maintenance, but most bunkers are like car batteries—they just wear out and need to be replaced every 2-3 years. Bunkers last 5-7 years.

“Greens and tee boxes can last longer if they’re well-built, up to 30 years,” he continued, “but because they get the most traffic and the most intense maintenance practices, they become less functional over time, so they have to be rebuilt. And with all of the advances in the development of Bermuda grass hybrids, especially the ultra-dwarf varieties, the goal is to end up with tees and putting surfaces that are firmer, more consistent and need less water than the originals.”

In recent years, Johnston has established an on-going relationship with The Landings Club on Skidaway Island just outside of Savannah, Georgia. The sprawling residential community boasts six private courses by big-name designers that were built amid the maritime forests and saltwater marshlands.

(Note to purists: While the oceanfront counties of Georgia generally share the Lowcountry’s climate and ecosystem, Skidaway is one of the state’s “Sea Islands” and part of its larger “Coastal Empire.”)

Starting in 2004, Johnston directed a $3-million refurbishment project on The Landings’ Plantation Course, which he and Byrd had designed in 1974, and the Palmetto Course by architect Arthur Hills, which opened in 1985.

“With both courses,” Johnston said, “we rebuilt the bunkers, added tees and pruned or removed some trees that had grown so much that they were literally ‘overshadowing‘ the greens. We also did some major improvement work on the irrigation systems and installed new concrete cart paths, which should last longer than the original asphalt.”

Last year, Johnston undertook a similar renovation of The Landings‘ Oakridge Course (Arthur Hills, 1988), including about six miles of new concrete paths. And like the Plantation and Palmetto jobs before, he added one new feature to the Oak Ridge layout that’s become par for the course, so to speak, in contemporary refurbishments.

“The Landings Club and other clients these days often want a new tee box built—usually a fifth tee on the course—specifically for senior men,” he said. “Even with better clubs and golf balls, we more ‘mature’ players just don’t hit it as far as we used to, but we’re not going to play from the ladies‘ tees. So that fifth tee gives us a face-saving option that avoids the longest forced carries and generally keeps us in the game. And the golf clubs have found that the lower-handicap women and competitive juniors like to use those in-between tees as well.”

Johnston also noted that The Landings Club maintenance staff had installed new Celebration Bermuda sod on all of the Oakridge fairways. This year he’ll return to the Plantation and Palmetto courses for some touch-up work. Johnston’s recent renovations in the Lowcountry include significant 2012 upgrades to the South Course at Moss Creek, which now sports rebuilt greens, new grasses on the fairways and practice-range improvements.

Over at Savannah Quarters, a private country-club community located just west of the city, the golf course posed a different type of “revival” challenge when the development was purchased by Greg Norman, the former PGA TOUR star who’s now a successful course designer and businessman. The existing Woodyard Course had been built by architect Robert Cupp.

Over at Savannah Quarters, a private country-club community located just west of the city, the golf course posed a different type of “revival” challenge when the development was purchased by Greg Norman, the former PGA TOUR star who’s now a successful course designer and businessman. The existing Woodyard Course had been built by architect Robert Cupp.

“Bob Cupp’s design was basically ‘target golf’ with lots of forced carries off the tees and to the greens,” said Savannah Quarters Director of Golf, Robert Stevenson. “That’s not Greg’s style at all. So he completely redesigned the course – the driving range became part of a new first hole and our practice facility is where No. 9 used to be. He turned a pair of nice par 4s into a great par-3/par-5 combination. He eliminated most of the carries in favor of ‘shoot-and-roll’ approaches to the greens, restored the site’s natural ponds, and rerouted all of the holes that used to be visible from the highway to create wooded buffers. It’s an entirely new course.”

Since reopening in 2006, the Savannah Quarters layout has become a popular local tournament host and centerpiece of a growing residential community. Norman sold his development interest to SunCal last year, which hired industry-leader Troon Golf Management to oversee club operations, but he still keeps an eye on changes to his signature course.

“Just last summer, some new homes were built along the 7th fairway and we had to establish a new OB [out-of-bounds] line that could have really narrowed the fairway. So we solved the problem, with Greg’s help, by creating a ‘collection area’—like a big waste bunker—on the other side of the fairway adjacent to the wetlands. The members were very pleased with the result.”

Back in the Lowcountry, Haig Point on Daufuski Island features a unique 20-hole course designed in 1986 by Rees Jones. The two additional par-3 holes and alternate tee boxes on a number of others give club members the option of playing from the less demanding “Haig tees” or the tougher but more scenic “Calibogue tees.” Jones came back to personally oversee a complete refurbishment of his design in 2007.

“The interesting thing about Rees Jones’ renovation here,” said Haig Point Director of Golf Jason Cherry, “is how it reflects his evolution as a designer over that 20 years or so. He’s moved to a more ‘US Open’ style, which means, for instance, lowering some of the greens and tightening up the bunkers around them. The overall effect is to enhance the visual quality of the course while making it more demanding, especially from the back tees. I think the course remains very playable for our members, but more challenging for lower-handicap players.”

Haig Point also has a unique golf amenity among Lowcountry courses—an additional regulation nine-hole course—that was built in 1988, but was not part of the Jones’ 2007 renovation work. “The Osprey Nine is very popular with our members,” Cherry said, “and they wanted it to retain its original character. We play fewer rounds on it, so it doesn’t get the same degree of wear. Like any course, you want to do regular improvements where necessary, but otherwise it’s a good example of leaving well-enough alone.”

Haig Point’s Osprey Nine, however, seems to be more the exception than the rule in the Lowcountry these days as the best private courses all over the region have been getting the “face-lift” treatment:

At Wexford Plantation on Hilton Head Island, Arnold Palmer completely renovated the club’s course in 2011, which had originally been built by designer Byrd in 1983. Palmer added new risk-reward options and other on-course enhancements, while retaining the acclaimed natural beauty of the setting.

Belfair in the Bluffton area near Hilton Head is home to a pair of top-rated courses by architect Tom Fazio. Both the East and West courses at Belfair have undergone significant refurbishments since 2010, including new bunkers on all 36 holes and new greens on the East Course. Belfair has also expanded its clubhouse and upgraded it practice facilities to incorporate state-of-the-art technology into the highly regarded learning center.

here Golf Club recently completed a two-year renovation of all 27 holes on its Fazio-designed course. The greens were rebuilt and topped with “mini-verde” ultra-dwarf Bermuda grass, while a new irrigation system that was installed will cut water usage by half.

Spring Island’s Old Tabby Links course underwent a major restoration in 2012. Originally designed by Palmer in 1991, the redo included widening fairways and enhancing greens and bunkers, but remaining true to the ruggedly scenic character that has made it a stand-out among Lowcountry private courses.

Dataw Island Golf Club completely recontoured and regrassed all of the greens on its Cotton Dike (Tom Fazio) course in 2011 and followed up with a similar refurbishment to its Morgan River (Arthur Hills) course in 2012 as part of an overall $5.4 million reinvestment in the club’s golf facilities.

Dataw Island Golf Club completely recontoured and regrassed all of the greens on its Cotton Dike (Tom Fazio) course in 2011 and followed up with a similar refurbishment to its Morgan River (Arthur Hills) course in 2012 as part of an overall $5.4 million reinvestment in the club’s golf facilities.

Dataw’s Director of Marketing, David Warren, is a transplanted Philadelphian who’s been a Lowcountry resident for 35 years. Like architect Clyde Johnston, he hails from a family of passionate golfers and is an enthusiastic advocate of the local game.

“The Lowcountry has some of the best private courses in the world,” Warren said. “Their designers are a “Who’s Who” of the business—Fazio, Jones, Nicklaus, Palmer, Hills and on and on. And the settings are incredibly diverse, from forests to meadows to wetlands, sometimes on the same hole. It’s a remarkably rich environment for golf and that’s why it’s so great that Dataw and the other clubs in the region are reinvesting to create this revival of Lowcountry golf. With the original developers gone, that responsibility has fallen on a new generation of club members and, if anything, they’re even more committed to preserving the quality of their golf courses.”

Like others interviewed for this survey, Warren noted two human enhancements that contribute to that “revival”: expertise and awareness. “You have to give a lot of credit to our course superintendents,” he said. “They have college degrees now in agronomy and other earth sciences. They know more about irrigation dynamics and natural fertilizers and hybrid grasses than you can imagine. They see a golf course as part of a larger ecosystem that they want to protect and extend for decades to come and they’re out there with their staff every day working to make that goal a reality.”

“All six of The Landings’ courses,” said architect Johnston, “are Audubon Sanctuary Program-certified and they’re very proud of that and they should be. Keeping that designation—even exceeding those environmental-protection standards when possible—is right at the top of my list when I take on a project at The Landings or anywhere else. I think it’s fair to say that all of us in this part of the golf business—designers, renovators, builders, landscapers, superintendents—understand our responsibility to do our jobs in a way that’s sensitive to nature.

“After all,” he concluded, “that’s why most of us came here to the Lowcountry in the first place: the clean air and water and beaches, the trees and the flowers and the wildlife. It’s a great place to raise your kids or enjoy your retirement. And to play golf. And I hope it’ll be like that a hundred years from now and that whoever is renovating one of my courses then will have the same perspective.”

Receive your complimentary Relocation guide and magazine